News ———— Memo

The forgotten asset class

In 1970-1971, there was a massive oversupply in commodities, leaving investors surprised when widespread commodity prices only a couple of years later more than doubled, and in some cases rose as much as five times. Shortly thereafter, in 1974-75, prices fell almost as drastically as they had risen, although not to as low levels as before the boom.

by Anna Svahn —

Forty-five years have passed since, and as I discussed in the first two memos, the markets have been fuelled by low interest rates and money printing making most assets look expensive (or inflated). But one asset class is yet to be inflated. In fact, after a decade or so of a bear market, they are not only cheap in relative terms, but in absolute terms as well. I’m talking about commodities, an asset class declared dead by most.

Note that when I am discussing the commodities market in this memo, I am referring to soft commodties and precious metals. They differ some from the more traditional industrial metals and the energy sector, since they are more contra cyclical to the stock market and like for example copper or oil, not an indicator for how well the economy is doing.

Dead markets

Investors have been warned many times before of so-called “dead” asset classes. In 1979 Business Week published a cover with the dramatic title “Death of Equities”. Since then, the S&P 500 is up almost 1000%. The equity market was in other means far from dead.

Equities are not unique in being declared dead. In 1998, Real Estate Investment Trusts were dismissed as “losing power to diversify a portfolio”. Shortly after that, The Economist wrote in 1999 that cheap oil would continue to be so. And the list goes on, in 2000, small value stocks were considered not having a future in the smart investor’s portfolio. In 2008, high-yield bonds tragically died in the financial crisis (at least that was what the New York Times said).

And today, 10 years later, Emerging Markets are questioned whether or not they make sense to invest in, and in true bubble spirit, we are also hearing from different sources that value investing is… (yes, you guessed it) dead according to CNBC.

The story continues with commodities. And I can’t really blame anyone for falling into the trap of only wanting to own the “best” asset class. The problem, however, that many investors seem to forget, is that we tend to choose the assets that have been performing best in the last few years, instead of looking for cheap bargains among the carcasses that are about to wake up from their long sleep in negative territories.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this memo, you should not only measure risk and opportunity by looking at historical returns but look at the investment risk by analyzing the future. We should know better than ignoring the fact that markets move in cycles, and learn how to identify the ones that are cheap, instead of buying what everybody else has been buying for the last decade.

After the asset classes mentioned above had been declared dead something interesting happened. They rose to live again.

Rise of the dead

What is the best way to identify a dead asset class? According to Ko and West (2020), an asset is usually declared dead after approximately three years of poor performance. What happens next is more exciting. Five years after an asset class has been declared dead, they have delivered gains in 88% of the time of an average of 80%, and in some cases up to 160%.

Five years after the “Death of Equities” cover in Business Week 1979, the S&P 500 was up almost 120%. After commodities were expected to stay cheap in 1999, prices went up 160% in the next five years. Buying a dead asset class has in other words been a good strategy throughout history.

The perfect storm

What we are witnessing today is not at all so different from the 1970s. One could argue that since commodity prices surged as a consequence of leaving the gold standard and hence being able to print money without it being backed by anything else than the “trust” in its value, the situation is different since we have since then never put the printing machine on pause. However, the similarity is to be found in the change of the amount we are printing now.

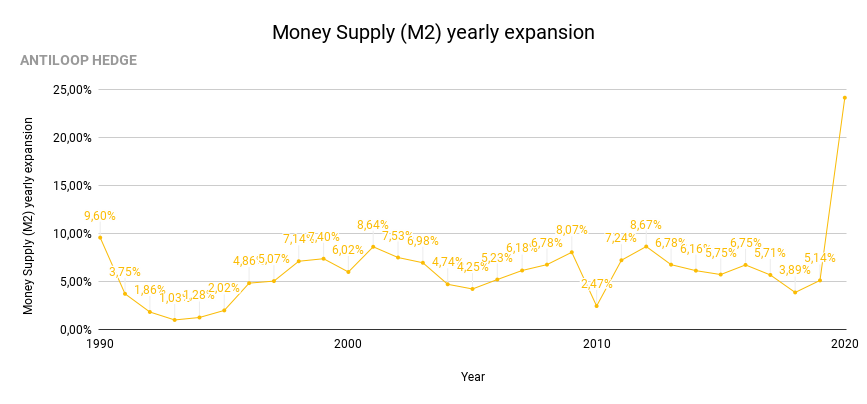

Up until 2020, the average yearly expansion of the monetary supply (M2) was around 5,5%. So far this year, the growth rate has been 24,16%.

This alone could have been a good indicator of where commodities are going next. But there are more factors speaking for the dead asset class awakening. I mentioned earlier that commodities are cheap, not only in relative terms to the stock market, but also in absolute terms. This could indicate that we are overdue a change in the market sentiment, but this is still not the biggest underlying reason to why it is a better time than ever to buy commodities.

Tech is not cutting production costs, yet

One common argument against investing in soft commodities is that technological development is moving so fast that we will be able to grow crops in a cheaper, faster, and more efficient way soon enough so that commodities prices will stay “lower for longer”.

I strongly disagree. At least in the shorter time horizon.

First of all, since commodities are cyclical and we have been in negative territory for more than a decade (although prices have started to rise again), the market is overdue for a run. But this is mainly a technical perspective, the fundamentals are more important to me.

When I researched the cost of production of commodities like corn and soybeans (including soybean meal and oil), I found something interesting. In 2010/2011, the cost of producing one acre of soybeans in the US was 368 USD. In 2017/2018, that had risen to over 640 USD. This price pattern can also be found in the cost of producing corn.

Other than that we are also facing climate challenges, as well as a growing population and in the future less space to grow our crops on. Even if technology might make it cheaper and more efficient to produce crops in the future, we are not there yet.

In reality, we are expecting a rising demand and even higher production costs as the quality requirements are going up. In addition, salaries are rising and companies have access to more capital meaning that the purchasing power is also going up.

It is a perfect storm for a commodity boom. And if you still do not believe me, just take a look at this: