News ———— Memo

The asset cult era

Suddenly, the Bitcoin maximalists choir went silent, and Peter Schiff kept screaming how right he had been all this time, calling out the crypto bluff, all while his pet rock still didn’t move up or down. The once so confident “you-can’t-put-a-multiple-on-a-tech-company” group bought dip after dip until their Mother Mary (Cathie Wood) wrote a letter to the Federal Reserve begging them to stop raising rates as she saw her Ark sink deep into the sea.

At some point in this crazy era of low rates and quantitative easing, market participants became so greedy they forgot the most important thing in investing: to manage risk.

The Swedish Riksbank just published a report saying market participants should not expect the central bank to help them as it is not the Riksbank’s role to facilitate for individual participants who have taken excessive risks.

The fourteen years following the financial crisis will go down in history as the short (but at the time pretty sweet) era of free money and high-risk appetite. While I do agree with the Riksbank that a central bank should not bail out individuals or corporates due to unsound risk-taking, I would still like to know how they would defend the past years of negative rates while promising that it would, in fact, not lead to inflation but, when it did, just pull the rug.

Money being free for over a decade has created a global everything bubble as investors had no other choice but to allocate money into high-risk assets to avoid negative yield on their savings accounts. But the escape into various markets that were not cash also created something else: a toxic asset-cult era.

While most high-risk asset classes rose together in perfect harmony, people clustered around single assets or asset classes, making up small cults that took every chance they got to claim the one asset they chose to invest in was the one that would generate the highest returns in the future. Free money and excessive liquidity from central banks had made investors’ risk tolerance so high that they no longer saw the risk of allocating most of their capital into one sector or sometimes just one asset.

But the inevitable happened, and money that had been free forever suddenly came at a price. With inflation, higher rates came, and so did sobriety in asset valuations.

Suddenly, the Bitcoin maximalists choir went silent, and Peter Schiff kept screaming how right he had been all this time, calling out the crypto bluff, all while his pet rock still didn’t move up or down. The once so confident “you-can’t-put-a-multiple-on-a-tech-company” group bought dip after dip until their Mother Mary (Cathie Wood) wrote a letter to the Federal Reserve begging them to stop raising rates as she saw her Ark sink deep into the sea.

At some point in this crazy era of low rates and quantitative easing, market participants became so greedy they forgot the most important thing in investing: to manage risk.

Risk and correlation

There is no such thing as a “best” asset or asset class. What really matters is your long-term portfolio performance. Fortunately, putting together a resilient strategy is not as hard as it might sound, but it is important to remember a few things to avoid the most common mistakes.

The first thing you need to keep in mind is that risk is the price you pay for potential return. The higher the expected returns, the higher risk. But unlike what many seemed to believe up until recently, after years of stimuli, high risk does not guarantee volatility solely on the upside.

The second thing you have to understand is that correlation is key. Traditional diversification focuses on value preservation rather than creation by complementing your equities portfolio with cash and bonds. But, as we have seen this year, it does not always offer protection against market downturns. Instead of using “safer” assets to preserve capital which might impact the long-term performance (as we have seen lately in the 60/40 portfolio), investors should focus on asset correlation relationships when assembling a diversified portfolio.

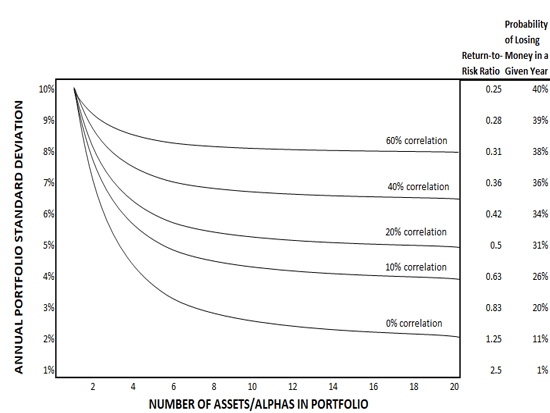

In his book Principles, Ray Dalio called diversification the “Holy grail of investing”. By combining fifteen to twenty good, uncorrelated return streams, Dalio found he could reduce his risks without reducing his expected returns.

Source: Principles, Ray Dalio

Diversification is not a new concept, yet so many investors misunderstand what it means and how to actually do it in a way that will protect you from volatility while not compromising on returns. In a study from 2016, the authors Renholtz, Fernbach, and Langhe found that many don’t see the benefit of diversification in terms of reducing portfolio volatility and that most instead believe diversification actually increases the volatility of a portfolio. This might be part of the explanation as to why so many cling to the false truth of long-term TINA.

The last and most important lesson is that the market could not care less about your ego. So do yourself a service and remove it from the calculation when deciding to own an asset or not.